Montana

Original Inhabitants

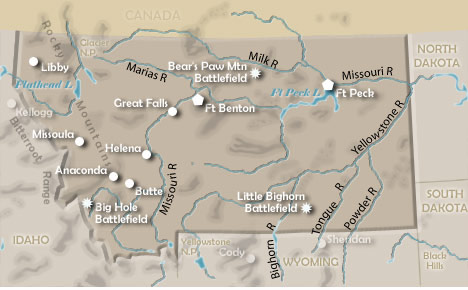

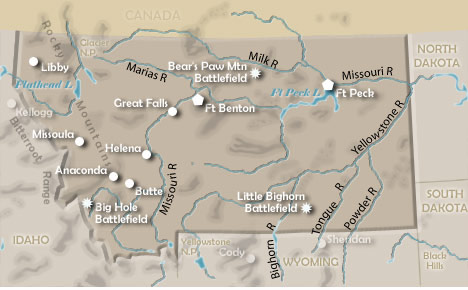

At the time of the first appearance of Europeans in what today is Montana, there were native inhabitants living in two geographical regions. In the plains area in the east, the Arapaho, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, Crow and Gros Ventre developed life styles revolving around the bison — their major source of food, clothing and shelter. In the valleys near the Rocky and Bitterroot mountains to the west, the Bannock, Kalispel, Kootenai and Shoshone found their homelands more conducive to agriculture.

Other tribes frequently spent a portion of the year in Montana, including the Cheyenne, Mandan, Nez Percé and Sioux.

The Early Europeans

French fur traders and trappers may have ventured into present-day Montana in the 1740s, but the evidence is not conclusive. Nonetheless, the area between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains was claimed by France and named Louisiana. French authority in the area was weakened by defeat in the French and Indian War and they compensated Spain, their ally in that conflict, by passing title to Louisiana to them. France temporarily regained control of the region during the Napoleonic Era, but in 1803 sold it to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase.

Explorers. President Thomas Jefferson`s curiosity about the newly purchased tract led to his support for an exploratory venture, fueled largely by the hope of discovering an easy water route that would lead to the Pacific Ocean. The Lewis and Clark Expedition set off in 1804 and reached the Forks of the Missouri River in present-day Montana the following July. The party again entered Montana on the return trip, splitting into northern and southern contingents in order to see more territory. The reports of Lewis and Clark at journey`s end were largely responsible for sparking interest in Louisiana, particularly in its abundance of fur-bearing animals.

Fur Traders.

Fur Traders. French and American traders and trappers had certainly visited the Montana area by the late 18th century, but Canadian François-Antoine Laroque left a record of his exploits along the Yellowstone River on behalf of the North West Company in 1806. The following year, Manuel Lisa, a Cuban who had relocated to St. Louis, established the first trading post, known variously as Fort Remon or Fort Lisa, on the Bighorn River. David Thompson, noted explorer and representative of the North West Company, established a post near Libby in 1807 and in other locations in later years. Although the number of white inhabitants in Montana remained small during the early decades of the 19th century, the competition among trading entities — the North West Company and its successor the Hudson`s Bay Company, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, the American Fur Company and others — was intense and served to deplete the animal populations by the 1840s.

The native populations of Montana both prospered and suffered from the fur trade with the Europeans. Indian life was improved by guns and tools received from the whites, but adversely impacted by exposure to alcohol and diseases against which they had no immunity,

Smallpox in particular.

Missionaries. The Flathead and Nez Percé sent representatives to the eastern United States in the 1830s for the purpose of requesting religious instruction, which touched off a wave of missionary activity. Some have viewed the Indian requests with some skepticism, speculating that the real aim was to receive the white man`s tools and medicines, not spiritual enlightenment. Several Protestant denominations sent missionaries into the West, but few found Montana to be appealing and most pressed on to the Oregon Country.

In 1841 Jesuit priest Pierre Jean De Smet, a Belgian by birth, ministered to the Flathead in the Bitterroot Valley. St. Mary`s Mission, near present-day Stevensville, probably was the first permanent white settlement in Montana; it was later sold to a private individual who operated it as a trading post.

Miners. A small gold strike was made at Gold Creek in 1858, but a series of more important finds was made after 1860. Gold was discovered in southwestern Montana along Grasshopper Creek in 1862 and in other locations in the following years. Boomtowns erupted at Bannack, Virginia City, Diamond City and Helena. Miners found relief from the drudgery of their work in the saloons and dance halls of the thriving towns. Once the gold had played out, the settlements were emptied of their residents as rapidly as they had filled up.

Lawlessness was a frequent feature of the Montana boomtowns and mining camps. Henry Plummer led an especially notorious gang, while also serving as the local sheriff. Unable to depend on law enforcement officials, many communities resorted to vigilante justice. Some employed the cryptic numbers 3-7-77 — to indicate the width, depth and length of the graves of those outlaws brought to justice. The numbers appeared in 1879 to warn "undesirables" to leave Helena. Plummer and about two dozen of his gang were eventually captured and hanged.

The Territorial Stage

Before achieving statehood, Montana was included by Congress in a long list of territories —

Louisiana,

Missouri,

Oregon,

Washington,

Nebraska, Dakota and

Idaho.

During these territorial years, settlement increased at a leisurely pace. The gold strikes of the 1860s brought many newcomers, most of whom moved on when the mines failed. However, the temporary increase in population sparked the arrival of the first railroad line, a regional organization that linked Fort Benton with Walla Walla in the Washington Territory.

Many prospectors arrived in Montana by steamboat, venturing up the Missouri River during the high water months of spring and early summer. Sufficient population developed during the gold rush years that Montana was granted separate territorial status in May 1864. Sidney Edgerton, an official in the Idaho Territory, was instrumental in gaining this designation and was appointed governor. Virginia City served as the territorial capital until it was moved to Helena in 1875.

Indian Wars

Even before the influx of whites during the gold rush years, efforts were made to promote harmony between the races. In 1851, a treaty was concluded at Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming. Among other provisions, recognition was given by the United States to a tribal homeland for the Crow along the Yellowstone River, the Assiniboine in northeastern Montana and the Blackfoot in the north central area.

Four years later, Governor Isaac Stevens of the Washington Territory began negotiation of a series of treaties designed to obtain the best lands for white settlers and assign the natives to less desirable reservation areas. A number of tribes signed such treaties under the enticements of financial support and promises of improvements for the reservations.

In the 1860s, clashes between the races became common as white miners encroached upon Indian homelands. Relations with the Sioux became particularly tense because the Bozeman Trail, which linked the Oregon Trail to the Montana gold fields, brought a steady stream of whites across Indian hunting grounds. Initial efforts to bring peace failed and ugly incidents continued to occur through the mid-1860s. However, a new government peace offensive resulted in the Fort Laramie Treaty with various Sioux bands in 1868. The Bozeman Trail was closed to white traffic and a number of the Sioux agreed to make their homes in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory, lands that they held sacred. However, disgruntled Sioux under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse remained in Montana.

Gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874 and miners quickly poured into the area in violation of the Sioux treaty rights and demanded protection from the U.S. Army.

In June 1876, the 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer was annihilated by Sioux and Cheyenne near the Little Big Horn River in southeastern Montana. This Indian victory was fleeting, however. Army reinforcements were dispatched to the area and Crazy Horse was forced to surrender in 1877; Sitting Bull held out for another four years before giving up his fight.

The last significant clash occurred in 1877 when U.S. forces pursued Nez Percé under Chief Joseph. The Indians won a costly victory in the Battle of Big Hole near the Continental Divide in southwestern Montana, but later surrendered most of their numbers at Bear`s Paw Mountain about 40 miles south of the Canadian border.

Economic Development in Montana

Livestock. Cattle had been brought into Montana from Oregon during the 1850s, but it was the demand for food from the gold miners of the following decade that created a thriving cattle industry. In 1866, Nelson Story drove a herd from Texas into Montana on the Bozeman Trail. The vast grasslands of the open range soon encouraged many other ranchers to try their luck.

Railroads provided the final boost to the growing cattle industry. A regional line, the Utah and Northern, reached Montana in 1880 and the

Northern Pacific, a transcontinental line, arrived three years later. Easy access to markets in other parts of the country made a number of the cattle ranchers wealthy.

All was not well, however. A challenge for use of the land was made by sheep herders who were also attracted by the lush grasses. Sheep are inclined to chew plants off at root level, leaving the land unusable for long periods. Armed clashes were frequent between the cattle and sheep interests.

The winter of 1886-87 created an economic disaster. Much of the land had already been overgrazed, then severe cold and storms wiped out over one-half of the cattle population and forced a change in the nature of the business. In later years, ranchers focused on maintaining smaller herds and kept them in enclosed areas. The era of the open range in Montana had ended.

Mining. The gold strikes of the 1860s played out quickly. A few of the miners turned to silver, but its extraction was more difficult and expensive to accomplish. The discovery of huge silver deposits near Butte in 1875 made its mining a more lucrative proposition, at least temporarily.

Silver mining interests were dismayed by the decision of the U.S. government of demonetize silver in 1873 — the so-called "

Crime of `73" in the minds of many Westerners. A huge deposit of silver was discovered in Montana later, but demand dropped, pulling prices down as well.

Further mining diversification was brought to Montana by Marcus Daly, one of the early silver miners. He was president of the Anaconda Company that became active in copper mining and was the chief competitor of

William Clark, the other great copper king" of the era. Their rivalry dominated the economy and politics of the state for years, but Anaconda emerged as the victor and extended its control beyond mines to electric power, railroads, newspapers, banks and timberlands.

Statehood

Montana`s territorial phase had been one of turmoil — livestock conflicts, Indian wars and wrangling between a Democratic electorate and governors appointed from Washington, D.C. Citizens groups tried on several occasions to press for statehood, but were not successful. A new constitution was prepared in 1889 and Montana was admitted as the 41st state by act of Congress on November 8. The new governing document had trimmed the power of the governor, a position first held by Joseph K. Toole. Helena became the state capital.

Montana`s agricultural and mining economy provided a base for

Populist political activity in the 1890s. Robert B. Smith was elected governor with Populist support and in later years

Progressive Era reforms were enacted, including mine safety laws, the

initiative and the

referendum. Women had been granted the right to vote in certain elections in 1869 and full suffrage was extended to them in 1914. Two years later, Jeanette Rankin, a feminist leader from Missoula, became the first woman elected to the House of Representatives. She later cast the only vote in opposition to American entry into

World War II.

Development in Montana was heavily influenced by federal legislation. Congress in 1909 passed the Enlarged Homestead Act, a measure that applied to public lands in a number of Western states. Under its provisions, the size of homesteads was increased to 320 acres, but homesteaders were obligated to cultivate 80 acres; forest and mining areas were excluded from this program. The law`s implementation resulted in an increase in farming and cattle operations in Montana.

The Era of the World Wars

Montana enjoyed initial prosperity during World War I, which brought a strong demand for wheat and other grains. However, a devastating drought in 1919 caused a sharp downturn in the state`s fortunes. Insect plagues and severe wind erosion extended the hard times into the

1920s. The resumption of farming operations in Europe caused a worldwide glut and plummeting prices for U.S. farmers. By the time of the stock market crash in 1929, Montana was already in a deep depression. Mining was also hard hit at this time because of competition from foreign sources; many mines and factories in Montana closed their doors.

The state benefited from a number of

The New Deal programs of the 1930s. The Fort Peck Dam was started in 1933, provided employment for 10,000 workers and eventually contributed to electric power generation and flood control on the Missouri River. Other programs brought the construction of new highways, the development of parks and recreation areas, and the spread of electricity into rural areas.

The federal government also made a major revision in its Indian policy during the 1930s. The Wheeler-Howard Act, also known as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, reversed the earlier practice of encouraging Native Americans to own land individually and decreasing the influence of the tribes. Under the new law, tribes were urged to write constitutions, institute tribal councils and engage in common business ventures.

The demands of waging

World War II brought a large measure of prosperity back to Montana, which supplied oil, lumber, meat and grains. Farmers did not enjoy good fortune for long after the war; prices dropped quickly, prompting an exodus from the farms to the cities.

Postwar Development

During the 1950s, the emerging aluminum industry brought growth to the state as did the discovery of oil in the eastern plains area. Power and irrigation were enhanced by the construction of the Yellowtail Dam (1961) on the Bighorn River and later the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River.

Tourism has played an increasingly important part in Montana`s economy. Building on the base provided by Yellowstone National Park (1872) and Glacier National Park (1910), the state and private ventures have developed year-round attractions — parks, dude ranches and resorts.

Coal mining and natural gas operations prospered during the energy crisis of the 1970s, but declining prices in the following decade ended the boom. In 1990, Montana lost one of its two seats in the House of Representatives, an event that many residents accepted as preferable to large increases in population.

Prominent political figures of recent times include the following:

- Mike Mansfield (1903-2001) was born in New York City, but moved as a child with his family to Montana. He enlisted as a seaman with the Navy at age 14 in World War I and later served in the army. After the war, he worked as a mining engineer, continued his education and eventually became a political science professor at Montana State University. He represented Montana in the House of Representatives from 1943 to 1953, then in the Senate until his retirement in 1977. Mansfield served as the Senate Democratic whip and later as majority leader. From 1977 to 1988, he was the U.S. ambassador to Japan.

- Marc Racicot (born 1948) is a Montana native and a graduate of Carroll College in Helena and the Montana Law School. He served in the armed forces for three years and became a county prosecutor. His early efforts at elective office were not successful, but in 1988 Racicot was victorious in a race for state attorney general. He was elected governor in 1992 and reelected four years later, and established a record for reducing the size of government and creating a budget surplus. In 2000, Racicot was named chairman of the Republican National Committee.

See also

Montana.